By Dotty Brown and Rick Stehlik

In an astounding achievement, the U.S. women’s eight-oared crew has won the gold medal in each of the last three Olympics. As it trains to extend that record to a possible fourth consecutive first-place finish in Tokyo, it’s worth reflecting back on how women broke into this “manly sport” – one seen as far too demanding for the “frail” Victorian woman.

Lottie McAlice — won a challenge match against another 16-year-old in 1870 on the Monongahela River. She won a gold watch in a much publicized race.

While there were “ladies boats” on the Schuylkill River in the 19th century, women rode in these wide barges as the men rowed. Occasionally a tomboy type with a rowing brother might try her hand at rowing. For instance, in the late 1860s, when Thomas Eakins was studying painting in Paris, he wrote letters home to his sisters suggesting they learn to swim well since they rowed so much.

And there were occasional spectacles, drawing crowds and headlines with the strange sight of women racing, which is what happened on July 16, 1870 on the Monongahela River near Pittsburgh when 16-year-old Lottie McAlice, the daughter of a boatman, raced two other teenage girls to win a gold watch.

Nonetheless, with an explosion of interest in exercise as a health benefit, Wellesley College near Boston in 1875 became the first women’s college in the country to launch a crew program. But its aim was largely to develop grace and rhythm. They rowed to music and poetry and would not race another school for nearly a century.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the country in San Diego, four women friends in 1882 began a club called ZLAC – the initials of their first names. Their first boat was a whaling barge. Largely a social club, they only bought their first racing shells in 1962.

Another early women’s rowing group sprung up in 1894 at the all-female Milwaukee-Downer College, which started out rowing in boats weighing about 325 pounds. In May 1913, they asked boat builder Racine-Truscott of Muskegon, MI, to build them two lighter boats for their intramural women’s crew.

“We believe we can decrease the free-board or depth by a strake, and possibly cut down the width by 2”, the company wrote back. That October, Downer christened its new boathouse and two boats, the Emily and the Louise, named for the mothers of the two women benefactors of its crew program. “The need of a new boathouse and boats has long been felt, and the Athletic Association takes great pride in this acquisition to its equipment,” the school publication, the Kodiak, wrote.

But in 1964, when Downer was absorbed into Lawrence University –which had no men’s crew program – women’s rowing went by the wayside. The women’s eight-oared shell of the time, the Katie was hung from the rafters of the university library. More than two decades would pass before Lawrence relaunched women’s crew, along with a program for men. Today, efforts are underway to restore the century-old Louise, a six-oared boat with coxswain.

Intramural women’s rowing also had a brief start in 1907 at the University of Washington “to maintain the health of the women… [and] to show them how to conserve their energy as to create in them skill, grace, confidence and endurance.” But by World War I, the program, which had sparked controversy, was gone.

The University of Pennsylvania also had intramural women’s rowing in the 1930s under coach Rusty Callow, and later in the 1960s, when it was coached by Joanne Iverson. “When I started coaching at Penn, one of the difficult things was we didn’t know how hard to make [women] train,” Iverson said in an interview. “We didn’t know what kind of weights they could lift. We didn’t know if they could run Lemon Hill and stay alive and be able to not

have a heart attack at it. We didn’t know any of these things and a lot of this had to be found out by trial and error.”

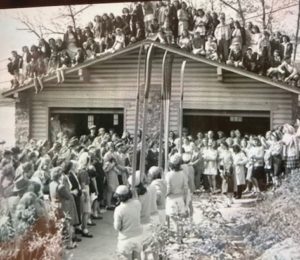

But women’s racing history really began in 1938 when a group of Philadelphia women launched the first competitive women’s rowing program in the United States. The Philadelphia Girls Rowing club was formed when a group of secretaries and clerks snagged one of the oldest buildings on Boathouse Row after learning that its owner, the Philadelphia Skating Club, was moving to Ardmore. But PGRC, with no other women’s program to compete against, could only race each other. The women initially were not taken seriously. Newspapers called PGRC a “marital club,” claiming the women just wanted to meet guys. And for decades, the all-male regattas treated them like a mascot, inviting them to lead off the races with an “exhibition row” down the river.

But finally, in 1956, PGRC found another crew to race against, in Florida, and from there, slowly women’s racing advanced. Mover-shaker Iverson as a young, ambitious PGRC rower in the early 1960s had been shocked to discover that women’s rowing was not an Olympic sport. She went on to establish the National Women’s Rowing Association to encourage the formation of women’s rowing programs at colleges and clubs.

Anita DeFrantz and Anne Warner race in the 1977 World Championships. The two competed in the eight in 1976, the first Olympics that allowed women. The eight finished with a bronze medal.

With pressure from European women, who had strong rowing programs before the Americans, the International Olympic Committee finally agreed to allow women’s rowing become an Olympic sport in the games of 1976. That summer, Joan Lind of California came in an astonishing second in the single, beating many of the steroid-pumped Eastern European rowers. The American women’s eight took bronze after East Germany and the Soviet Union.

The U.S. did not compete in the 1980 Moscow Olympics, but in 1984, the U.S. women’s eight – now drawing on the strength of a decade of collegiate women supported by Title IX—won gold. It repeated that feat in 2008, 2012, and 2016.

Let’s see what happens in 2021.

Dotty Brown is the author of “Boathouse Row, Waves of Change in the Birthplace of American Rowing.”

Rick Stehlik is a veteran of 60 years rowing on Schuylkill, and modeler of racing shells.

On the eve of the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games, join the HOSR Committee 50 and past Olympians for a conversation about the journey to the biggest stage and how Philadelphia played a role in their success. Our sixth ‘Story Hour’ will take place via Zoom on Wednesday, July 21, 7:00pm. Register here in advance.